Critical econometrics - a brief note on the current state of quantitative economics

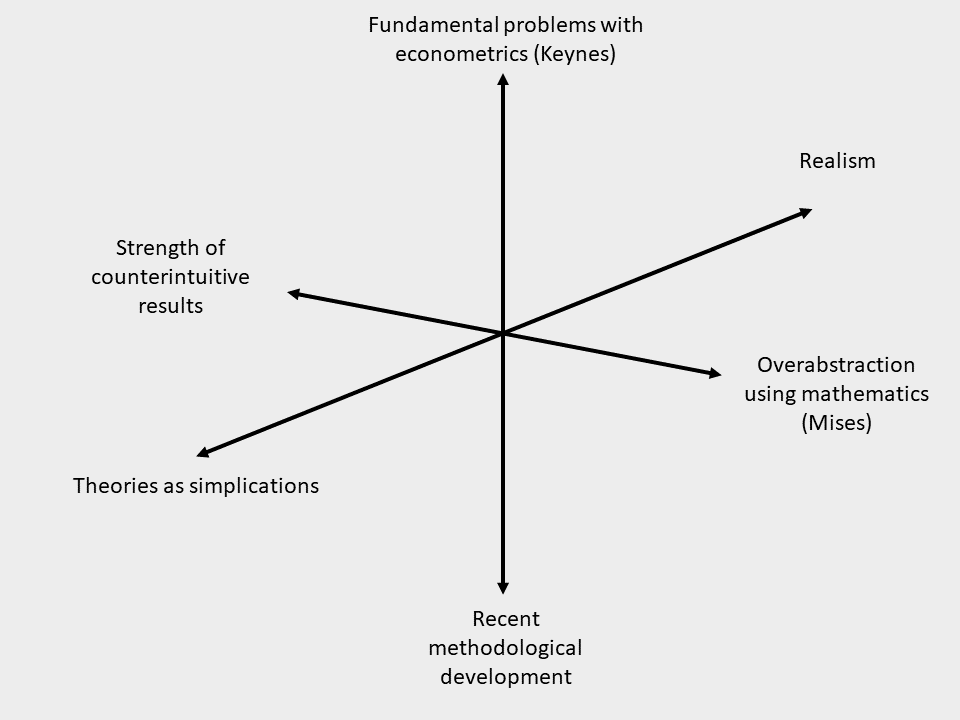

Recently, a group of students and academicians raised their concerns about the current state of economics, especially the way it is taught in academia (1–3). Many of the criticisms raised are not new and go back to Keynes’ and Mises’ well-known objection against a quantitative approach to economics (see Figure 1 for an overview of some of these critiques and their counter-arguments). The authors of Thinking like an Economist? find it particularly troubling that economics students in the Netherlands are primarily being taught quantitative and mathematical research skills. This parallels a growing tendency towards technical complexity in current economic practices. Yet, it contrasts sharply with Keynes’ scepticism towards quantitative economics as a viable field of interest:

No one could be more frank, more painstaking, more free from subjective bias or parti pris than Professor Tinbergen. There is no one, therefore, so far as human qualities go, whom it would be safer to trust with black magic. That there is anyone I would trust with it at the present stage or that this brand of statistical alchemy is ripe to become a branch of science, I am not yet persuaded. But Newton, Boyle and Locke all played with alchemy. So let him continue. (4 p. 156)

Is the modern field of econometrics really closer to alchemy than to science as Keynes argued? Certainly, some of Keynes’ critiques are still valid; in today’s terms econometrics is still hampered by problems of endogeneity, instability, non-stationarity, unknown functional forms, measurability and data dredging (5–7). Nevertheless, since those early beginnings new methods such as instrumental variables, difference-in-difference, vector autoregressive and (spatial) panel models and the rise of big data have added a whole new array of tools to overcome these problems. Despite its difficulties and the inevitable cost new methods come at, the field of econometrics is constantly evolving in pursuit of better techniques to study economics.

Secondly, the use of formal models and abstraction in theory has raised concerns about the real-world implications of economics as a science. For Mises and Austrian economists in general, the language of mathematics and econometrics is too confining since it does not allow to express and test notions of causality, respectively (8). Certainly, we should not let the applicability of mathematical and statistical methods define the scope of economics. Moreover, we should be very wary of mathematically tractable and elegant but absurd theories (a good example is the family of rational addiction theories) (9). Just as correlation does not imply causation, mathematical tractability does not necessarily explain human actions.

Yet, there is still much to say in favour of formalism. Mathematical methods can relieve the cognitive burden of conceptual and qualitative modelling. While without doubt, there are very intelligent people in economics, intuition and common sense might not be adequate for understanding the complex interactions and trade-offs in the real economy (10). A certain level of formalism allows us to more accurately formulate, question, and study economic processes (9). Keep in mind, though, that whether a finding is intuitive or not should not be taken as an indicator of its validity (11). Apart from counter-intuition and complexity, the human mind is also vulnerable to story-telling. Our subjective feeling of understanding makes us susceptible to believing good stories without evidence and ignoring evidence without a story (9).

Thirdly, economic models are always simplifications of reality. While this is surely problematic for policy makers working on real-life problems, it can hardly be avoided. Capturing the complex behaviour of the real economy would warrant the use of extensive models consisting of numerous equations (such as computable general equilibrium models)—eventually only to become unwieldy or as inconsistent and chaotic as reality itself (12). To quote Dani Rodrik: “Models are never true; but there is truth in models. We can understand the world only by simplifying it.” (13)

Figure 1 Trade-offs in economic-econometric modelling

Figure 1 Trade-offs in economic-econometric modelling

The previous paragraphs have hopefully shown that all hope for quantitative economics is not lost. While misapplication of formal methods in economics is a problem, those methods do have their value—when applied properly—and should not be discarded altogether. The question that remains, though, is how to proceed. To end, therefore, I want to offer some suggestions that might avoid quantitative economics from turning into a purely academic discipline.

Firstly, it is always a good idea to complement quantitative models with qualitative or conceptual models that allow for “a full, verbal explanation of the theory” (9,10) in order to (i) avoid foolish assumptions (e.g. to make models tractable, or ideologically minded “intuitions”) and “mathematical gymnastics” (8), (ii) to make models more comprehensive (given limitations in modelling), and (iii) to think of contradictory evidence. Secondly, the comparison of descriptive statistics (14) with simple and state-of-the-art econometric methods allows to put results into perspective and helps recognising methodological artefacts and spurious correlations. Lastly, we should recognize the importance of context; to quote Dani Rodrik again: “The correct answer to almost any question in economics is: It depends.” (13) Insofar economists do not already do so, they should leave their ivory towers and obtain the field expertise needed for correct model building and application (15).

As a final word, I want to stress I have only added my two cents on the usefulness of quantitative economics, a topic which is likely to remain controversial in the future. However, even if mathematical models and econometrics are alchemy or black magic, they might still serve a purpose, as the following fragment from Roger Martin du Gard’s Lieutenant-colonel de Maumort seems to suggest:

One day, M. Renan, having voiced his agreement with the friends who were gathered that afternoon, and having condemned even more indignantly than the others, with proofs, anecdotes, unpublished documents to support him, the stupidity, the naivety and above all the abominable cruelty of the leading revolutionaries, did a very surprising about-face, and pointed out that these monsters with human heads had nevertheless been the architects of an imposing and highly civilizing piece of work. Then, generalizing, he presented the idea that, in the current state of humanity, certain essential reforms perhaps cannot be accomplished by reason, moderation, justice. In short, he made the case for the usefulness of the fanatical and the violent: “One must accept them,” he said. “Let them do their ugly job, and then, as soon as possible, get rid of them …” He smiled, delighted with his idea. “Who knows if this hideous collaboration of evil is not indispensable for the coming of a great good? Criminal and abhorrent, insane and detestable, they certainly are. But the endeavor that humanity is dimly trying to perfect, and that goes beyond them, and that is glorious, needs their madness and their crimes to blossom and to establish itself in a lasting way. (16 p. 292)

References

- Heijne S. Weten economen eigenlijk wel genoeg van economie? De Correspondent [Internet]. 2018 May 8 [cited 2018 Sep 16]; Available from: https://decorrespondent.nl/8248/weten-economen-eigenlijk-wel-genoeg-van-economie/1054571282864-d02b91f2

- Van Der Linden MJ. Ons economieonderwijs is waardeloos. Follow the Money [Internet]. 2018 May 7 [cited 2018 Sep 16]; Available from: https://www.ftm.nl/artikelen/ons-economieonderwijs-te-smal-te-abstract-en-te-wiskundig

- Tieleman J, De Muijnck S, Kavelaars M, Ostermeijer F. Thinking like an Economist? Rethinking Economics NL; 2018 Mar.

- Keynes JM. On a method of statistical business-cycle research. A comment. The Economic Journal. 1940;50(197):154–6.

- Israel F. Keynes’s Critique of Econometrics Is Surprisingly Good [Internet]. Mises Institute; Available from: https://mises.org/wire/keynes%E2%80%99s-critique-econometrics-surprisingly-good

- Keynes JM. Professor Tinbergen’s method. The Economic Journal. 1939;49(195):558–68.

- Boumans MJ. Econometrics: The Keynes-Tinbergen Controversy. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2015;

- Garrison RW. Mises and His Methods. In: Herbener JM, editor. The Meaning of Ludwig von Mises. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1993. p. 102–17.

- Rogeberg O. Taking Absurd Theories Seriously: Economics and the Case of Rational Addiction Theories. Philosophy of Science. 2004 Jul;71(3):263–85.

- Krugman P. Two cheers for formalism. The Economic Journal. 1998;108(451):1829–36.

- Diener E, Lucas R, Helliwell JF, Helliwell J, Schimmack U. Issues Regarding the Use of Well-Being Measures for Policy. In: Well-being for public policy. Series in Positive Psychology; 2009. p. 245.

- Borjas GJ, Van Ours JC. Labor economics. McGraw-Hill/Irwin Boston; 2010.

- Rodrik D. Economics rules: The rights and wrongs of the dismal science. WW Norton & Company; 2015.

- Goertzel T. Econometric modeling as junk science. The Skeptical Inquirer. 2002;26(1):19–23.

- Boumans M. Methodological institutionalism as a transformation of structural econometrics. Review of Political Economy. 2016 Jul 2;28(3):417–25.

- Du Gard RM. Lieutenant-colonel de Maumort. Alfred A. Knopf; 2000. 777 p.